The Hopkins Ultraviolet Telescope (HUT) was a NASA-funded telescope whose specialized

purpose was to explore the Universe using the technique of low-resolution spectroscopy in the

far-ultraviolet (850 - 1850 Angstrom) spectral region. The project grew out of the JHU sounding rocket program

and was selected for development in 1978 along with two other ultraviolet-sensitive telescopes that flew as

a Spacelab package called the Astro Observatory. Professor Arthur F. Davidsen of the Henry A. Rowland Department of

Physics and Astronomy at JHU was the Principal Investigator for the HUT project.

The Hopkins Ultraviolet Telescope (HUT) was a NASA-funded telescope whose specialized

purpose was to explore the Universe using the technique of low-resolution spectroscopy in the

far-ultraviolet (850 - 1850 Angstrom) spectral region. The project grew out of the JHU sounding rocket program

and was selected for development in 1978 along with two other ultraviolet-sensitive telescopes that flew as

a Spacelab package called the Astro Observatory. Professor Arthur F. Davidsen of the Henry A. Rowland Department of

Physics and Astronomy at JHU was the Principal Investigator for the HUT project.

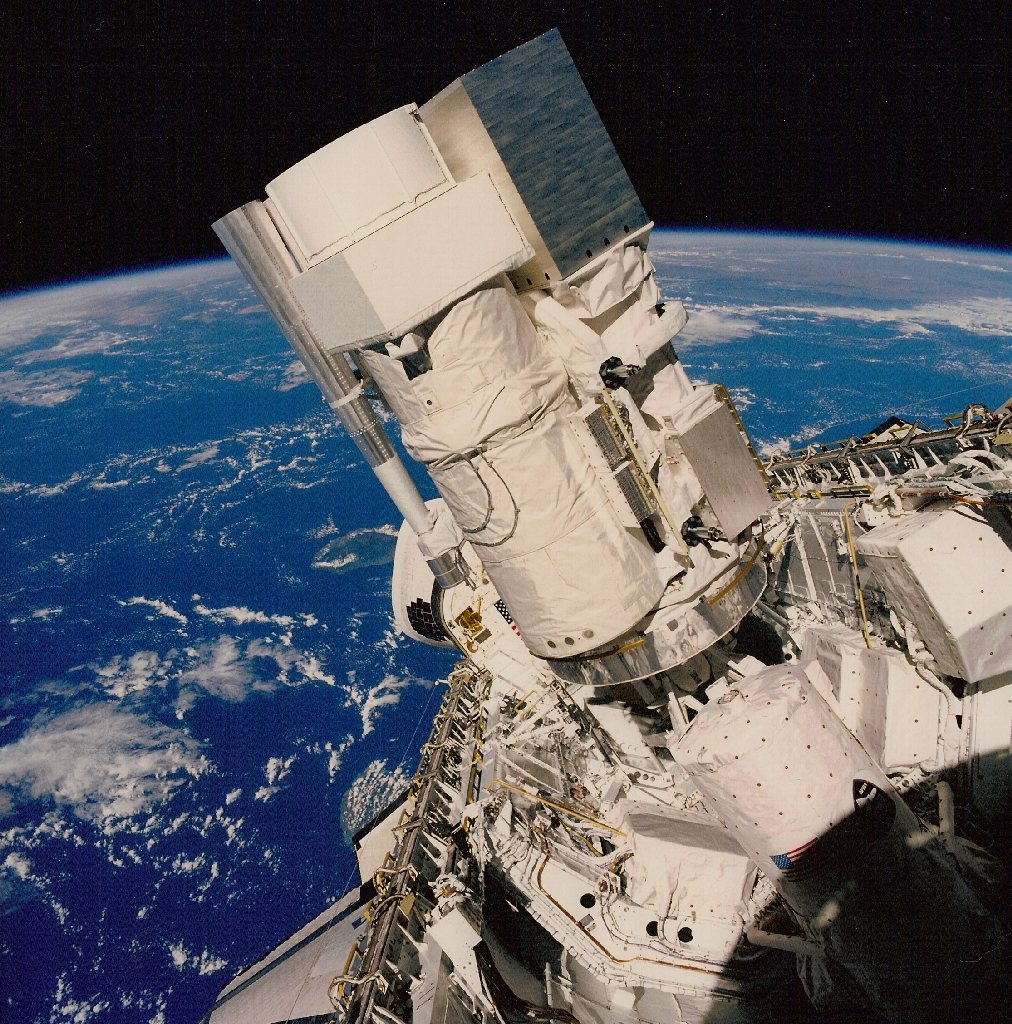

HUT and the Astro Observatory were ready for launch in March of 1986 to observe Halley's comet

and many other astronomical objects, but the flight was delayed because of the Challenger disaster

of Jan. 28, 1986, the flight directly preceding the Astro mission. Originally rescheduled for an early 1990 flight,

the Astro-1 mission suffered a series of delays due technical problems with the space shuttle, and finally launched on

STS-35 (Columbia) on December 2, 1990, for a 10 day mission. Despite a number of technical glitches (including

with the Spacelab Instrument Pointing System that pointed the telescope package), HUT obtained unique data on some

90 targets.

HUT and the Astro Observatory were ready for launch in March of 1986 to observe Halley's comet

and many other astronomical objects, but the flight was delayed because of the Challenger disaster

of Jan. 28, 1986, the flight directly preceding the Astro mission. Originally rescheduled for an early 1990 flight,

the Astro-1 mission suffered a series of delays due technical problems with the space shuttle, and finally launched on

STS-35 (Columbia) on December 2, 1990, for a 10 day mission. Despite a number of technical glitches (including

with the Spacelab Instrument Pointing System that pointed the telescope package), HUT obtained unique data on some

90 targets.

HUT was planned to be flown on numerous shuttle missions, but because of the backlog after the Challenger disaster,

even a second flight of the payload was not guaranteed. However, quick publication of scientific results from

Astro-1 were convincing, and a second flight was scheduled. HUT was upgraded for the second mission, and

Astro-2 (STS-67 on Endeavour) launched on March 2, 1995, for a two-week mission, the longest mission flown as of that date.

Astronauts including payload specialist Samuel Durrance from JHU, operated the payload around the clock

during the mission and some 275 astronomical targets were observed during Astro-2.

During both missions, a cadre of support scientists from JHU Physics and Astronomy and from the JHU

Applied Physics Laboratory were resident at NASA-Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, to

support the real-time mission operations.

HUT was planned to be flown on numerous shuttle missions, but because of the backlog after the Challenger disaster,

even a second flight of the payload was not guaranteed. However, quick publication of scientific results from

Astro-1 were convincing, and a second flight was scheduled. HUT was upgraded for the second mission, and

Astro-2 (STS-67 on Endeavour) launched on March 2, 1995, for a two-week mission, the longest mission flown as of that date.

Astronauts including payload specialist Samuel Durrance from JHU, operated the payload around the clock

during the mission and some 275 astronomical targets were observed during Astro-2.

During both missions, a cadre of support scientists from JHU Physics and Astronomy and from the JHU

Applied Physics Laboratory were resident at NASA-Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, to

support the real-time mission operations.

Of the many scientific results published using HUT data, the one that stood out was the detection of

a partially-ionized intergalactic medium using the ultraviolet light from a distant quasar as a

background source. This key observational result was one of the driving scientific goals for HUT in the

original proposal to NASA in 1977, and it came to fruition with observations made during Astro-2 in 1995!

Because of the importance of this result, the Smithsonian Institution requested that HUT be

enshrined in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. HUT was transferred to the Smithsonian

in March 2001, and now proudly hangs on display in the Exploring the Universe gallery.

In addition to the treasure trove of data obtained on Astro-1

and Astro-2, one of the legacies of the HUT project is that many of the participants have gone on to

hold key roles in numerous other NASA missions and projects, including the

Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer mission, the Hubble Space Telescope, and

the James Webb Space Telescope project, among others.

Please visit the following link for more information about the history of the HUT project, the data

from both missions, the photo archive from both missions, and much more:

Please visit the following link for more information about the history of the HUT project, the data

from both missions, the photo archive from both missions, and much more: